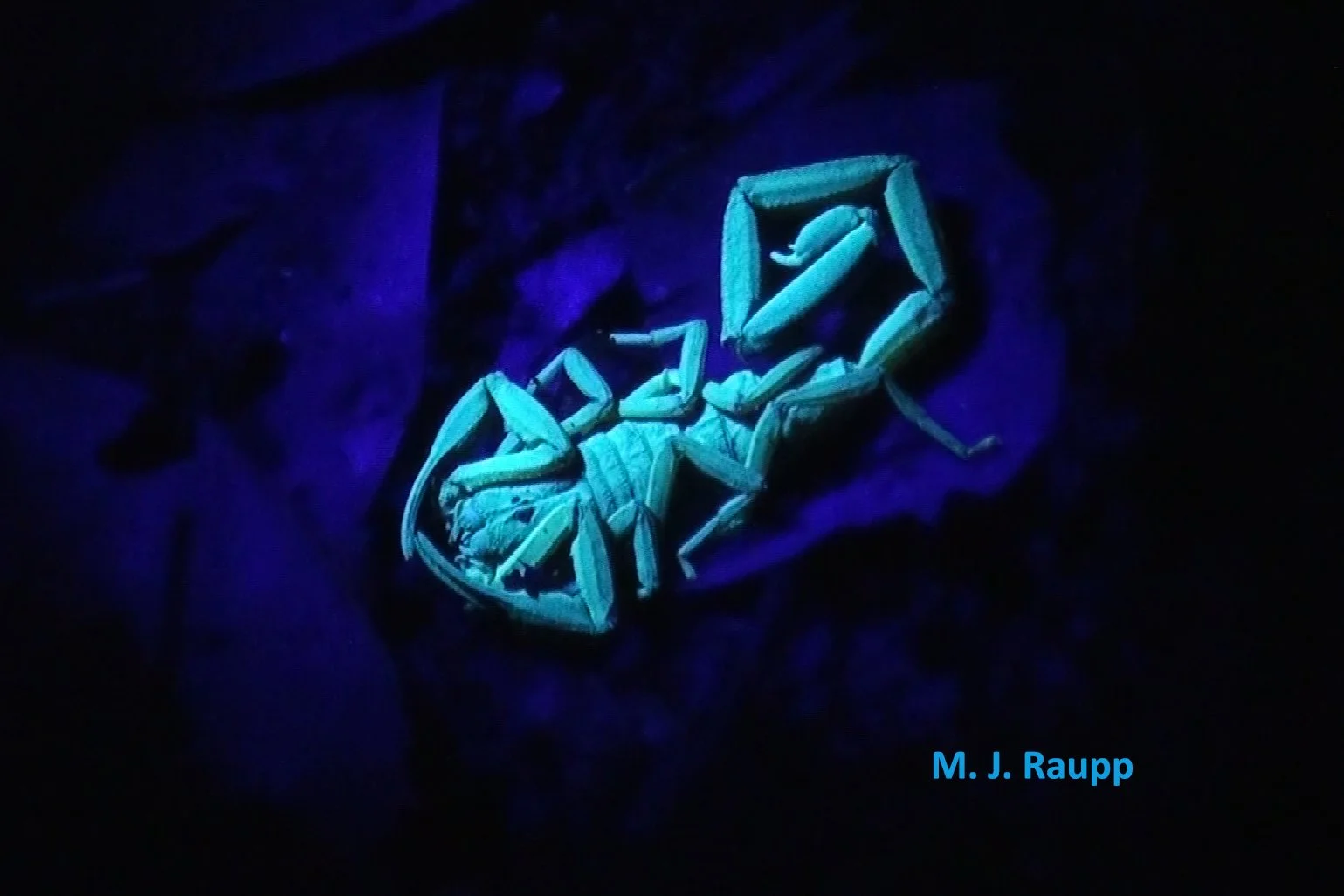

In previous episodes we visited tasty termites and beautiful butterflies during the daylight hours in the rainforest of Belize. This week we go dark on a nocturnal foray into the heart of a tropical rainforest. This escapade can produce memorable encounters. During one such foray we were amazed to see a beautiful brown scorpion turn a gorgeous blue-green when a trail guide moved a fallen leaf and cast the beam of a blacklight on the scorpion. Being a youth of the 60’s, I was instinctively struck to understand what my blacklight posters shared with this stinging eight-legged rainforest predator. It turns out that blacklight posters contain compounds, phosphors, capable of capturing the high energy photons of UV light and releasing their energy in longer and less energetic forms of visible light, producing dazzling, glowing hues. Scorpion glow results when UV light is captured by two compounds, beta-carboline and 4-methyl-7-hydroxycoumarin, found in the scorpion’s exoskeleton. Once captured, UV’s energy is released in the form of eerie blue-green florescence.

Scorpions are not insects. They belong to another part of the arthropod clan called arachnids and are relatives of spiders and ticks. The scary pinchers on the front end of the scorpion are its pedipalps. They are used for grasping and dismembering insects and spiders that comprise most of the scorpion’s meals.

In a series of clever studies, Dr. Douglas Gaffin and his colleagues discovered that the scorpion’s entire body may act as a photoreceptor or universal “eye” used to detect different levels of light. Light in the UV range directed at scorpions produced bouts of rapid movement. These researchers suggested that the scorpion’s whole-body “eye” might help it move to places where light no longer illuminates its body, such as locations beneath vegetation where the searching eyes of larger predators were less likely to spot it. Whole-body photoreceptors might also be used by scorpions to detect the waning light levels of twilight, the signal to exit hideouts and start their nocturnal hunt for prey.

A failed attempt to capture a rather large scorpion on the rainforest floor provided a memorable sting to my right thumb. A second successful attempt with my left hand let us get up close and personal with this powerful nocturnal predator. Its sharp stinger delivers a witch’s brew of neurotoxins and other pain-enhancing compounds. Under the glare of white and red flashlights the scorpion’s color was a chocolate brown. But under the beams of a UV-black light, the scorpion fluoresces an eerie blue-green. UV light receptors on the scorpion’s body may help it detect sunlight and initiate movement to dark hiding places during daylight hours, or they may help the scorpion detect the absence of sunlight, signaling the safe time to emerge from cover to hunt prey during the cloak of night. Video credits: M. J. Raupp and Asmita Brahme

The business end of the scorpion is the sting, an enlarged segment at the end of the scorpion’s tail that contains a venom gland and a needle-like poker to deliver the poison. The sting is used to immobilize and kill prey and as a means of defense against larger animals. For some inexplicable reason, I was moved to pick up a scorpion we discovered on a rainforest trail while searching for reptiles. My first attempt to grab the scorpion by its tail was a miss that resulted in a painful and memorable sting to my right thumb. The pain was similar to that of a large wasp or honeybee. It lingered for several minutes then dulled to a mild nuisance for a few hours. A novel element of this misadventure was notable swelling to my thumb which lasted through the next day. As seen in the video, my second attempt to capture the scorpion using my left hand was a success. Holding this largish rascal was a bit scary but pretty good fun. I learned that scorpions move surprisingly fast, but the venom of this Centruroids scorpion is not generally life threatening. However, some relatives of Centruroids, including those in the genus Tityus, are very dangerous and their venom can be fatal to humans. This is not an endorsement for anyone to hold a scorpion as reactions to any foreign protein, including scorpion venom, can be serious and sometimes life-threatening.

If this sting gets you, you will be sending out an SOS to the world.

On another tropical adventure in the rainforests of Belize I had the good fortune to encounter scorpions in a somewhat different context. After a long day of feeding mosquitoes and avoiding crocodiles with a group of students on a study abroad, the prospect of enjoying a little shut eye in the bunkhouse was most appealing. Unfortunately, one student climbed into her lower bunk bed and was surprised to see a rather impressive scorpion beneath the mattress of the upper bed just a few inches above her head. She tested the potency of the scorpion’s sting when she grabbed the one lurking over her bunk and was stung. She summarily hurled said scorpion out the door of her cabin. Her assessment of the experience: “It only hurt a little and that thing was really annoying me”. You go girl!

On the steps of a pyramid at Caracol, students from the University of Maryland explore the wonders of tropical rainforests and Mayan civilizations. Image: Luis Godoy

Acknowledgements

We thank the hearty crew of BSCI 339M, Belize: Tropical Biology and Mayan Culture, for providing the inspiration for this episode. Thanks to our guide Ren for discovering a scorpion on the rainforest floor. Special thanks to Asmita for sharing the video of a bug geek nervously capturing a rather large scorpion. Luis Godoy graciously provided the image of the students at Caracol. Many thanks to Dr. Jeff Shultz for an enlightening discussion about scorpion glow. The fascinating article “Scorpion fluorescence and reaction to light” by Douglas D. Gaffin, Lloyd A. Bumm, Matthew S. Taylor, Nataliya V. Popokina, and Shivani Manna provided much background information for this episode.